This was the first of two projects completed in the Cryptogamic Herbarium at the NHM, working with Curator of Lichens, Dr Holger Thüs. With one of the largest lichen collections in the world at 400,000 specimens, and at least 10,000 type specimens, it was an unmissable opportunity to learn more about these fascinating organisms, about the historical and current curation of lichen collections, and to hone my skill at reading handwriting through the ages.

At the NHM the lichens are divided physically into British and Worldwide. The survey provided data on:

- The geographical distribution of British lichens in the collection

- Collection and acquisition of the specimens as recorded on the specimen labels

- The prevalence of the various methods of mounting and storage used.

Analysis of the data will allow a comparison of the geographical distribution of specimens in the collection with national databases to assess significance. The depth and accuracy of information about the specimens already held on the NHM database can be reviewed and the information will help in planning resources needed for future collection management projects and digital databasing.

The British lichen collection is stored in 7 walls of cabinets, some wooden, some metal.

A randomised sample of 100 store locations was generated, making sure there were no duplicates.

For a single species at each location, data was recorded for 2 sample specimens, one at the top left of the first sheet in the first folder and the second sample from the bottom right of the last sheet in the last folder. In total, therefore, approximately 200 specimens were examined (some species only having one specimen).

Information recorded for each specimen:

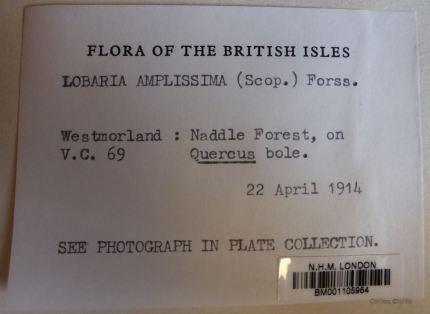

Barcoding specimens improves their accessibility by making information about them on the database searchable and linking them to other associated data or specimens.

Barcodes were added where missing. Specimens had only been barcoded previously if they were particularly important eg type specimens, or culturally significant, or if they had been accessed for particular purposes such as research projects.

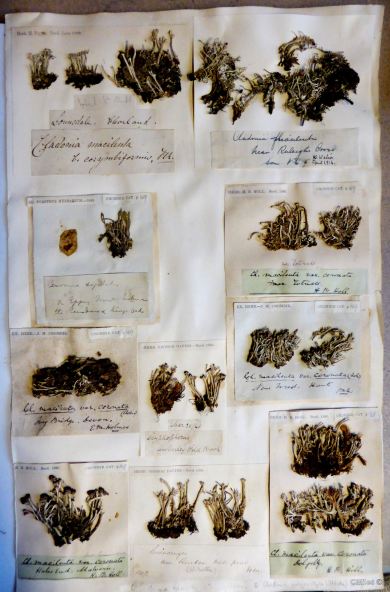

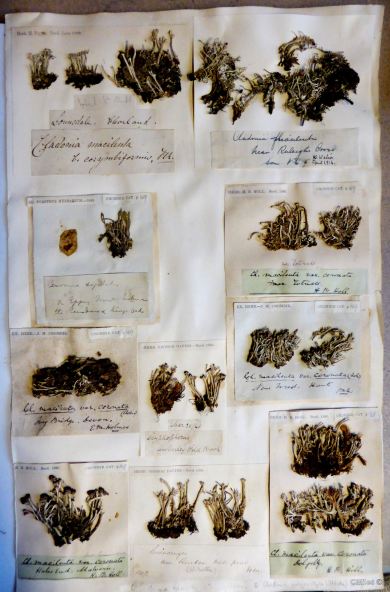

- Species name on folder and on specimen label

The species name on the folder is Acrocordia conoidea, but the name on the specimen label is the now superceded name of Verrucosa epipolea.

- Vice-county number and name if present, and other locality information from which the vice-county might be identified

Vice-counties were introduced in 1852 – this one looks as if it was possibly added to the label more recently.

Vice counties are divisions based on the ancient counties of Britain used for biological recording. They are similarly sized geographical units which are independent of local government reorganisations and allow data collected over long periods of time to be compared.

Early collectors sometimes gave just the name of a house or wood. Working out where they might be from provided some interesting historical detective work!

- Collector, year of collection and herbarium owner

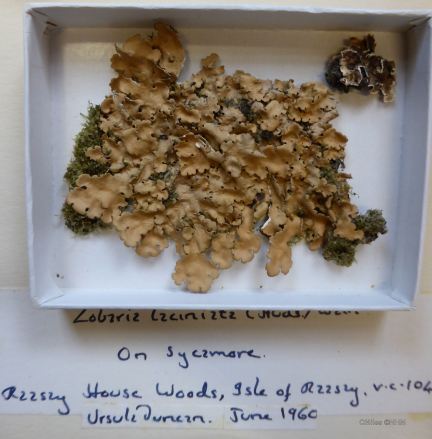

The earliest recorded sample was 1790 from the Herbarium of Rev Hugh Davies. It was frustrating when the full date wasn’t given – does ’60 refer to 1760, 1860 or 1960?

Other information about how the lichens were mounted included whether the label was typed or handwritten.

A significant amount of data was recorded about the state of the storage of the specimen.

It was recorded whether the specimen was on a sheet marked as being on on permanent loan from Kew. There is a permanent loan arrangement with Kew which means all (non-lichenised) fungal collections were transferred from the NHM to Kew with a reciprocal transfer of algae, lichens and bryophytes from Kew to the NHM.

Other questions were …

… is it glued directly to the sheet, as here, or in a packet glued to a sheet.

If so do the ends of the packet fold under as here – and make the lichen vulnerable to damage when opened?

… or with ends folded over on top, so the specimen is easily accessible.

Best of all, is the specimen in a packet which is not glued to anything, but can be stored 4 packets to a folder, and easily accessed?

Finally, how many collections are on the sheet? Not always an easy question to answer when there may be more than one ‘collection event’ under a single label.

When planning a review like this, its worth bearing in mind the time taken to:

- Physically locate and transfer samples

- Decipher handwriting, and revisit previous records when something becomes clear

- Identify locations : http://www.cucaera.co.uk/grp5/ is recommended as a tool for finding vice counties from a place name, grid reference or postcode. It also provides a zoomable map with vice county boundaries clearly marked.

I’m very grateful to Dr Holger Thus for this opportunity.